Review of the EU Migration and Asylum Pact

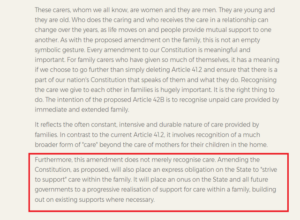

1) A review of the timeline for the implementation of the new EU Migration and Asylum Pact

In July 2019, both formal and informal meetings commenced within the Council of the European Union to discuss the future of the EU’s migration and asylum policy

On the 22nd of November 2019, the Council published the Finnish Presidency report titled “way forward for EU migration and asylum which included comments such as “The rhetoric we use in our policymaking is equally relevant; this is reflected in the debate on the Dublin Regulation. There is a shared understanding that the current system is not suitable for securing a fair distribution of asylum seekers across Member States.”

On the 4th of December 2019, the EU Home Affairs Ministers commenced discussions on the future of EU Migration and Asylum on the basis of the Finnish Presidency Report, confirming a need for a comprehensive approach to migration, with a whole-of-government and whole of route approach.

On the 23rd of December 2020, the European Commission presented the new pact on migration and asylum and five new legislative proposals to reform the EU asylum rules.

In June 2021, the Council presidency and European Parliament representatives reached provisional agreement on an EU asylum agency regulation, including turning the European asylum support office (EASO) into a fully-fledged EU asylum agency, responsible for improving the functioning of the common European asylum system

On the 9th of December 2021, the European Council adopted the asylum agency regulation, noting that Ireland voluntarily opted into this regulation on the 27th of March 2023

On the 19th of January 2022, the new EU asylum agency started operating

In June 2022, the European Council approved negotiating mandates on Eurodac and screening regulations, which were based on proposals set out in the new EU Migration and Asylum Pact.

On the 8th of June 2022, the European Council reached agreement on key asylum and migration laws, noting that this was the first formal step towards updating the EU’s migration and asylum laws to streamline the asylum procedure across the EU, including the modification of the Dublin Regulations and introducing new solidarity mechanisms.

In October 2022, EU Member States representatives reached agreement on what was said to be the final component of a common European asylum and migration policy, that would allow member states to address situations of crisis in the field of asylum and migration by adjusting certain rules around the registration of asylum applications, and also facilitating requests for solidarity and support measures.

On the 20th of December 2023, the Spanish presidency of the Council and the European Parliament reached a deal on the core political elements of five key regulations that will (in their words) “thoroughly overhaul the EU’s legal framework on asylum and migration”.

On the 8th of February 2024, EU member states’ representatives approved the provisional deal that was reached between the Council presidency and the European Parliament on 20 December 2023.

On the 27th of March 2024, Minister for Justice, Helen McEntee TD, sought and secured Cabinet approval to seek the necessary approvals from the Houses of the Oireachtas to opt-in to the measures in the EU Migration and Asylum Pact including the 5 pieces of law needed to realise the aims of the pact.

The next step are as follows:

a) In accordance with Article 29.4.7 of the Constitution, the Government must obtain the prior approval of both Houses of the Oireachtas, where it wishes to opt-into any measure in the area of freedom, security or justice (which includes immigration and asylum) – noting that Helen McEntee has stated that she wants to seek this formal approval from both Houses of the Oireachtas as soon as possible (so this may happen inside the next couple of weeks).

b) The laws approved by the EU Member States in February 2024, must be formally adopted by the European Parliament and the Council and according to the European Councils website, this “is expected before May 2024”.

c) Once the regulations are formally adopted Ireland can either do nothing, in which case the regulations will not be applicable to Ireland, or choose to formally opt-into the laws, after which time, it will not be possible to opt out.

d) If or when Ireland opts-into the 5 Regulations, one of two things could happen (and so far I have not been able to determine which path we will be required to take)

Path 1: is that the 5 Regulations simply become law in Ireland on a set down, which would be stated in the respective regulations. In this case, after the Houses of the Oireachtas vote to opt-into the Pact, the Dail and the Seanad would have no further role in the legislative process (this is called the directly effective path); or

Path 2: is that some or all of the 5 Regulations would have to be transposed into domestic law, meaning that some or all of the regulations would have to go through the normal 5 stage Dail and 5 stage Seanad process and thereafter be signed by the President (this is called the transposition path)

– noting that we favour the transposition path over the directly effective path, because the transposition path greatly increases the amount and type of legal avenues opened to us to challenge the regulations.

2) To explain the difference between transposing laws and directly effective laws and why it is so important which applies to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact

The laws that the EU wish to implement to enact the goals set out in the EU Migration and Asylum Pact, could be done by means of either regulations or directives, noting that the EU have opted for regulations in this case, and as I said earlier, the EU have proposed 5 number regulations to enact the goals set out in the Migration Pact.

So, what is a Regulation?

A Regulation is a piece of law that, almost exclusively, has binding legal force throughout every Member State and enters into force on a set date in all the Member States – meaning that regulations are directly effective without national parliaments having to enact domestic laws.

Directives, on the other hand, lay down certain results that must be achieved but each Member State is free to decide how to transpose directives into national laws.

So if these proposed laws were introduced by means of Directives, we would definitely be required to introduce domestic legislation to transpose the EU laws into law in Ireland, and this would potentially give us an opportunity to challenge the domestic laws if or when they were passed by both Houses of the Oireachtas and there would even be a possibility that the President might refer the Bills to the Supreme Court or a petition lodged with the President to call an Ordinary Referendum.

However, in normal course – regulations do not require domestic laws to be enacted, so there is a possibility that the 5 number EU Migration pact regulations will never become Bills in Ireland, instead they will be enacted as directly effective Regulations by the EU, and these Regulations will bind Ireland and every other member state on a date stipulated in the regulations, without Ireland having to enact any domestic law.

The reason I say there is a possibility the regulations will not have direct effect (as is the normal course) is because Helen McEntee has stated on a number of occasions, in response to parliamentary questions that “Member States are beginning to prepare their transposing legislation and operational systems for the Pact to go live in 2026, two years after its anticipated adoption. In order for Ireland to effectively align its law and systems with other Member States, and to implement a more cohesive migration system provided by the Pact, it is my intention to bring proposals concerning an opt-in to Government next month.”

So, Helen McEntee is talking about a requirement for transposing legislation and as I have said, this is usually only required for directives, not regulations. As stated, I have not been able to determine with certainty just yet whether the 5 regulations will need to be transposed or not, but I am leaning towards not, not least because regulations are almost exclusively directly effective, but also because each of the 5 number regulations at the final article of each regulation includes an article titled “Entry into force and applicability” – and states “This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in the Member States in accordance with the Treaties”

If the regulations are directly effective, serious questions would need to be asked of Helen McEntee as to why she has been suggesting otherwise, given that there are fewer mechanisms open to challenge the regulations if they are directly effective.

3) To explain the laws that it is proposed to introduce to enact the aims of the EU Migration and Asylum Pact and whether these laws are favourable to Ireland or not

As I have said, the EU proposes to enact 5 regulations to enact the aims of the EU Migration and Asylum Pact. The first regulation that we will look at is called:

1) The Eurodac Regulation: Eurodac is an EU database that stores the fingerprints of international protection applicants, or people who have crossed a border illegally and has been in operation since 2003. Through the new Eurodac Regulation (which is over 200 pages long) the EU intend to create a new computerised central database of biometric data, alphanumeric data and, where available, a scanned colour copy of identity or travel documents, as well as of the electronic means of transmission between Eurodac and the Member States. The purpose of the Eurodac Regulations is said to be to make it easier for Member States to determine responsibility for examining an asylum application by comparing the fingerprints of asylum applicants and non-EU/EEA nationals (from the age of 6 years and above) against a central database; and enable law-enforcement authorities to consult Eurodac for the investigation, detection and prevention of terrorist or serious criminal offences.

Because Ireland is not bound by EU law in the area of immigration or asylum, recital 98 of the regulation specifically makes reference to the fact that Ireland is not taking part in the adoption of this Regulation and is not bound by it or subject to its application (unless of course we voluntarily opt-in).

While the introduction of the Eurodac Regulation seems reasonable, I would note two points:

a) Given that many people (myself included) believe that the EU would like to track the movements of all citizens if possible, once the infrastructure for such a system is up and running for one group of people, it is easily extended to cover all people, so you should question how long before such a system is proposed to be used for EU citizens too; and

b) The Eurodac Regulation calls for a study on the technical feasibility of adding facial recognition software to Eurodac within 3 years of the regulation entering into force, including for minors – again once the infrastructure is established, it is easily extended to cover all peoples – to ensure non discrimination and equality of treatment.

2) The Screening Regulation: As matters currently stand, Regulation 2016/399 applies to persons crossing the external borders of member states that are party to the Schengen acquis. The Schengen Area is the name given to a region of Europe where there are no border checks between countries. Ireland is not part of the Schengen Area, which means that if you travel to the Schengen Area from Ireland, you pass through an immigration checkpoint and have to show your passport or national identity card. The proposed new Screening Regulation is said to further develop Regulation 2016/399 to also include for screening of third country nationals who:

a) are apprehended in connection with an unauthorised crossing of the external borders,

b) are disembarked following search and rescue operations , and

c) who make an application for international protection at a border crossing point without fulfilling entry conditions.

So, the new Screening Regulation is said to strengthen the control of persons at external borders, including faster identification of the correct procedure – such as return to their country of origin or start of an asylum procedure.

Because Ireland is not bound by EU law in the area of immigration or asylum, recital 47 of the regulation specifically makes reference to the fact that Ireland is not taking part in the adoption of the Regulation and is not bound by it or subject to its application (unless of course we voluntarily opt in).

3) The Asylum Procedure Regulation: As matters stand Directive 2013/32/EU is the current procedure used for granting and withdrawing international protection at an EU level. It is said that although there are common standards for asylum procedures across the EU, there are still significant disparities between the Member States as regards the types of procedures used, the recognition rates, the type of protection granted and the level of reception conditions and benefits given to applicants of international protection. The purpose of the new Asylum Procedure Regulation (which is over 200 pages) is therefore said to be to ensure that third country nationals and stateless persons are examined in a procedure which is governed by the same set of rules, regardless of the Member State where the application is lodged to ensure harmony of treatment of applications for international protection. This regulation provides for issues such as in-person interviews, the right to legal counselling, legal assistance and representation, assessment of special procedural needs, guarantees for minors, medical examinations, age assessment procedures, the process for making and examining an application for international protection etc.

With respect to the Asylum Procedure Regulation, I would note the following particular concerns:

Firstly, there are new more restrictive requirements for determining both first countries of asylum and safe countries (both of which could have a significant impact on our ability to return international protection applicants to other countries). These concerns include, the fact that the country the applicant is being returned to must either have ratified and respect the Geneva Convention, or that the person being returned to the safe country would:

a) be allowed to remain in the third country, and

b) be given access to an adequate standard of living, and

c) be given access to healthcare; and

d) be given access to education

– in addition to the usual conditions such as life and liberty not being threatened on account of race, religion etc and that the applicant faces no real risk of serious harm etc.

And the second significant concern is while the regulation says that Member States retain the ability to designate safe third countries in addition to those designated at an EU level, a Member State cannot designate as a safe country, a country that the EU has designated otherwise.

I would exercise extreme caution in opting into the Asylum Procedure Regulation noting both the extensive requirements a country must meet to be deemed either a first country of asylum or a safe country and also the fact that we would no longer have control over what we consider to be a safe country – noting that both of these changes would likely make it significantly more difficult for Ireland to return international protection applicants to other countries.

4) The Asylum and Migration Management Regulation. The purpose of this regulation is twofold.

a) to modify some of the criteria for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection, therefore leading to the full repeal of the Dublin Regulations and

b) to establish a solidarity mechanism (including financial payments) to support Member States who receive more asylum claims than others due to their geographical locations .

Broadly speaking, the Dublin Regulations are based on the principle that the first Member State where fingerprints are stored or an asylum claim lodged is responsible for processing a person’s asylum application. There have been calls to overhaul this system for years as it is felt that certain countries benefit more from the regulations that others, with Ireland being a prime example, as given our geographical location, it is quite likely that a person will have made an application for international protection in another EU country, before journeying to Ireland – thus giving us the legal right to transfer that person back to the other country where they sought international protection or journeyed to first.

As part of the Asylum and Migration Management Regulation, the EU want to repeal the Dublin Regulations. That said, the new regulation will, in broad terms, maintain the same rule that an asylum seeker will be required to apply for protection in the first member state that it enters, however, as I said earlier, the new regulation will also introduce a mandatory solidarity mechanism which will force Ireland to either:

a) accept relocation of a minimum of 30,000 asylum seekers annually, from other member states regardless of the fact that Ireland is not the first member state that the applicant entered (note that the figure of 30,000 is said to be the minimum figure that can be accepted annually), or

b) if Ireland decides that it does not want to or cannot accept 30,000 asylum seekers annually, we would have to pay a monetary contribution (they use the word contribution, but this payment would clearly be a mandatory penalty) of €20,000 per person, which would cost Ireland a minimum of €600m per year but these figures are subject to change, including increase, or

c) offer alternative solidarity mechanisms in the form of operational support such as deployment of resources, or measures focused on capacity building, or provision of facilities and technical equipment, provided however that the value of these alternative supports will be calculated to ensure that the member state has expended sufficient monies

Because Ireland is not bound by EU law in the area of immigration or asylum, recital 81 of the regulation specifically makes reference to the fact that Ireland is not taking part in the adoption of the Regulation and is not bound by it or subject to its application (unless of course we voluntarily opt in).

So, while much of the Dublin Regulation criteria will be maintained, it doesn’t actually make a difference as Ireland would be required to accept a minimum of 30,000 asylum seekers annually (regardless of the fact that the applicants would not have arrived in Ireland first – thereby completely disregarding the central tenets of the Dublin Regulations ) or pay a penalty of at least €600m annually.

5) The Crisis and Force Majeure Regulation. So the purpose of this regulation is to facilitate adjustment or derogation from certain rules in situations of migratory crisis or force majeure with respect to the Asylum and Migration Management Regulation and the Asylum Procedure Regulation – noting that these are the 2 regulations that I would be most concerned about. The adjustments or derogations would relate to the registration of asylum applications, the asylum border procedure, and to requests for enhanced solidarity and support measures from the EU and other member states.

In essence this regulation states that upon receiving a request from a member state advising that it is in a situation of migratory crisis, the European Commission would assess the request and make a decision, and where appropriate, make a proposal for a European Council implementing decision which would include a draft Solidary Response Plan including items such as the amount of funds to be taken from the solidary contributions, and assessing whether the funds in the solidarity fund are enough to cover the crisis situation, and if not, the amount of additional funds needed from member states. Where the effected member states has requested relocation of asylum seekers as the primary or only solidary measure that can address the crisis, the Commission can consider this. Whatever derogations the effected member state is successful in securing can apply for up to 12 months. This regulation also provides that a member state in crisis is relived of its obligation to take back an international protection applicant where that member state has been determined as the member state liable for the applicant.

- To explain why Ireland is not legally required to enact the laws under the EU Migration and Asylum Pact

In general, the law of the European Union applies to all 27 member states. However, occasionally member states negotiate certain opt-outs or opt-in’s to or from legislation or treaties of the European Union, meaning they do not have to participate in certain policy areas regardless of what laws the EU may put in place across the EU. Currently, only three member states have such opt-outs or opt-in’s:

- Denmark(2)

- Ireland(2)

- Poland (1)

The United Kingdom had four before leaving the EU.

For the purpose of this video, we are only concerned with the opt-in’s that Ireland has.

So when laws are enacted at an EU level in the area of freedom, security or justice, Ireland is not legally bound by any such laws, unless we specifically and voluntarily opt-into those laws.

The opt-in provision with respect to freedom, security and justice was originally obtained by Ireland and the United Kingdom in a protocol to the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997, with the opt-in being retained by both Ireland and the UK with the passing of the Treaty of Nice in 2002 and the Treaty of Lisbon in 2008. This opt-in provision is referred to as Protocol 21.

To understand what is included in the areas of freedom, security and justice – you must go back to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union which was signed in 1958, in which Articles 67-89 confirm that freedom, security and justice include the following policy areas:

- Asylum;

- Rules concerning external borders;

- Immigration policies and policies concerning third countries’ citizens;

- Combating illicit drugs;

- International fraud;

- Judicial co-operation in civil matters;

- Judicial co-operation in criminal matters;

- Customs co-operation; and

- Police co-operation for preventing and fighting terrorism, drugs trade etc.

What this means is that Ireland is not bound by EU law in the areas of immigration or asylum, but where the EU makes a legislative proposal in these areas (such as the current proposed EU regulations on migration and asylum), Ireland has three months to decide whether they wish to opt-into discussions. If they do not opt-in, they are deemed to have opted-out, and discussions simply go ahead without them. Any legislation which is adopted then binds the other Member States – but not Ireland.

That said, once the proposed laws have been formally adopted by the EU, Ireland can, at any time thereafter voluntarily opt-into those laws, noting that if Ireland opts-in to any such laws, there is no mechanism by which they can later opt out.

At this stage most people are familiar with the fact that Ireland is not bound by EU immigration and asylum law unless we voluntarily opt-in, however, I expect that most people are unfamiliar with how this opt-in is legislated for or how it has changed over the years, so a little bit of history is important here:

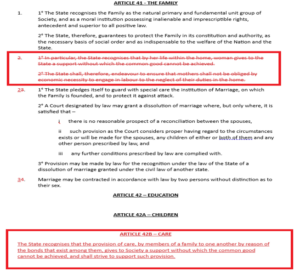

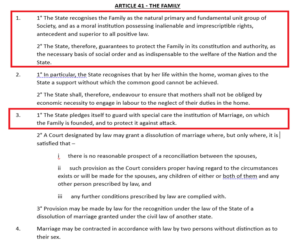

As I said earlier, the opt-in provision with respect to freedom, security and justice was originally obtained by Ireland and the United Kingdom in a protocol to the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997, and this opt-in provision was enshrined in law, following the passing of a Referendum called the 18th Amendment of the Constitution Bill, 1998 – Treaty of Amsterdam, which inserted the following at Article 29.4:

“The State may ratify the Treaty of Amsterdam amending the Treaty on European Union, the Treaties establishing the European Communities and certain related Acts signed at Amsterdam on the 2nd day of October, 1997.

The next section is the part that refers to the opt-in provision –

The State may exercise the options or discretions provided by or under Articles 1.11, 2.5 and 2.15 of the Treaty referred to in subsection 5° of this section and the second and fourth Protocols set out in the said Treaty but any such exercise shall be subject to the prior approval of both Houses of the Oireachtas”.’

So, there are two important things to note with respect to the opt-in provision,

a) it says that “the state may exercise the options or discretions provided” and

b) it says that the State may only exercise the options or discretions if it secures the prior approval of Both Houses of the Oireachtas.

This opt-in provision was carried forward in the Constitution on the passing of a Referendum called the 26th Amendment of the Constitution Bill, 2002 – Treaty of Nice, which inserted the following at Article 29.4

“The State may ratify the Treaty of Nice amending the Treaty on European Union, the Treaties establishing the European Communities and certain related Acts signed at Nice on the 26th day of February, 2001.

The next section is the part that refers to the opt-in provision –

The State may exercise the options or discretions provided by or under articles 1.6, 1.9, 1.11, 1.12, 1.13 and 2.1 of the Treaty referred to in subsection 7° of this section but any such exercise shall be subject to the prior approval of both Houses of the Oireachtas.

There was no significant difference between the wording arising from the Amsterdam Treaty and the Nice Treaty with respect to the opt-in provision.

But then came the second Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, noting that the Referendum on the 28th Amendment of the Constitution (Treaty of Lisbon) Bill 2009, included several new provisions such as reaffirming our commitment to the EU and delegating further power to the Government in terms of the opt-in provision under Protocol 21.

So, on the passing of the Lisbon Referendum, new Article 29 of the Constitution read as follows, noting that this is the current wording of the Constitution:

“Ireland affirms its commitment to the European Union within which the member states of that Union work together to promote peace, shared values and the well-being of their peoples.

The State may ratify the Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, signed at Lisbon on the 13th day of December 2007 (“Treaty of Lisbon”), and may be a member of the European Union established by virtue of that Treaty.

No provision of this Constitution invalidates laws enacted, acts done or measures adopted by the State, before, on or after the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, that are necessitated by the obligations of membership of the European Union referred to in subsection 5° of this section or of the European Atomic Energy Community, or prevents laws enacted, acts done or measures adopted by—

i the said European Union or the European Atomic Energy Community, or institutions thereof,

ii the European Communities or European Union existing immediately before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, or institutions thereof, or

iii bodies competent under the treaties referred to in this section,

from having the force of law in the State.

7° The State may exercise the options or discretions—

i to which Article 20 of the Treaty on European Union relating to enhanced cooperation applies,

ii under Protocol No. 19 on the Schengen acquis integrated into the framework of the European Union annexed to that treaty and to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (formerly known as the Treaty establishing the European Community), and

iii under Protocol No. 21 on the position of the United Kingdom and Ireland in respect of the area of freedom, security and justice, so annexed, including the option that the said Protocol No. 21 shall, in whole or in part, cease to apply to the State,

but any such exercise shall be subject to the prior approval of both Houses of the Oireachtas.

So, signing up to the Treaty of Lisbon did (at least) 3 important things, including:

a) Reaffirming Irelands commitment to the European Union

b) Providing that EU Law would be supreme over Irish law, including the Irish Constitution regardless of whether the law in question was enacted before, on or after the Treaty of Lisbon came into force, on the basis that no law or administrative act which was necessitated by Irelands Community law obligations or membership could be found to be unconstitutional (this is often referred to as the necessitated obligations clause).

c) Not only reaffirming that the People had delegated authority to the Government to opt-to EU laws in the area of freedom, security and justice, but also extending the power of the Government to allow them to relinquish the opt-in provision entirely, if they could secure approval from both Houses of the Oireachtas.

So, what all of this means is that:

a) Ireland is not bound by any laws enacted by the EU in the areas of freedom, security or justice, which includes immigration and asylum, by virtue of Protocol 21 introduced by the Treaty of Amsterdam, carried forward by the Treaty of Nice and retained by the Treaty of Lisbon

b) The power to opt-into laws in the area of freedom, security and justice, which includes immigration and asylum, was delegated to the Houses of the Oireachtas through the Treaty of Amsterdam – meaning the Houses of the Oireachtas, and not the People decide whether we sign up to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact

c) If or once the Houses of the Oireachtas agree to opt-into laws in any of these three policy areas, and in circumstances where the Government thereafter communicate our opt-in to these laws to the EU, there is no mechanism to opt-out of these laws into the future

d) It is also possible that once we opt-into these laws, the necessitated obligations regarding EU law supremacy will become live – meaning that any legal challenge mounted after opting into these laws would likely fail as EU law may be deemed supreme over the Irish Constitution

e) If all of that wasn’t bad enough, the State, on approval from both Houses of the Oireachtas can completely relinquish the opt-in provision, again without having to seek approval from the people or hold a referendum, because the People delegated this authority to the Houses of the Oireachtas with the Treaty of Lisbon Referendum in 2009

In addition to all of this, it should be noted that while the people were being asked to vote on the Treaty of Lisbon and to further extend the power of the State to relinquish our opt-in provision, the Government gave a declaration to the EU, which was incorporated into the Treaty of Lisbon, which stated the following:

“Ireland affirms its commitment to the Union as an area of freedom, security and justice respecting fundamental rights and the different legal systems and traditions of the Member States within which citizens are provided with a high level of safety.

Accordingly, Ireland declares its firm intention to exercise its right under Article 3 of the Protocol on the position of the United Kingdom and Ireland in respect of the area of freedom, security and justice to take part in the adoption of measures pursuant to Title V of Part Three of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to the maximum extent it deems possible.

Ireland will, in particular, participate to the maximum possible extent in measures in the field of police cooperation.

Furthermore, Ireland recalls that in accordance with Article 8 of the Protocol it may notify the Council in writing that it no longer wishes to be covered by the terms of the Protocol. Ireland intends to review the operation of these arrangements within three years of the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon.”

A declaration similar to this has been submitted by the Irish Government numerous times through the years, firstly, upon the passing of the Treaty of Amsterdam, to as recently as June 2016, within 2 weeks of the UK voting to leave the EU. That said, the declaration given at the time of the passing of the Treaty of Lisbon is far more significant given that through this declaration, the Government not only signalled their intention to opt-into laws in the area of freedom, security and justice to the maximum extent possible but they also told the EU that they would review the entire opt-in provision within 3 years of the Treaty of Lisbon, noting that in the Lisbon Treaty referendum the State asked the People and were granted by the People the authority to relinquish the opt-in provision entirely without the need for a further referendum.

I am unsure if the People were aware of the declaration the State made to the EU at the time of the Lisbon Treaty, and how significant it was to delegate their authority to the Government to relinquish the opt-in provision in 2009. Its also worth noting that when the opt-in provision was negotiated in 1998, it was the UK who were pushing for the opt-in, with Ireland being a reluctant partner at the time. It was accepted by all that the opt-in would need to apply to both Ireland and the UK otherwise it could have destroyed the Common Travel Area and erected new barriers to travel between the UK and Ireland. So in 1998 Ireland elected to make a declaration to the EU to make clear the fact that it was a reluctant partner to the UK in terms of the opt-in protocol, and at this time (in 1998) Ireland voluntarily declared that it would revisit the opt-in provision into the future.

Finally, just to close out on the opt-in protocol, all of Protocol 21 opt-in’s that the Government have exercised are recorded and can be viewed on the GOV.ie website noting that from the year 2000 to 2010 the Government exercised 16 out of 72 opt-in’s, whereas from the year 2010 to date the Government have exercised 71 out of 82 opt-in’s, noting that as time progresses, the Governments opt-in rate is becoming significantly higher.

5) The final area we will look at is – steps we can take to try and stop this pact becoming law in Ireland.

Step 1: Contact your TD’s and Senators to ask them to vote no to the opt-in to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact

On the 8th of February 2024, EU member states approved the provisional deal that was reached between the Council presidency and the European Parliament on the 20th of December 2023, in relation to the 5 EU Migration and Asylum regulations and thereafter on the 27th of March 2024, Minister for Justice, Helen McEntee TD, sought and secured Cabinet approval to seek the necessary permissions from the Houses of the Oireachtas to opt-in to measures in the EU Asylum and Migration Pact – meaning the next stage will be to secure permission from both Houses of the Oireachtas to opt-into these new laws, so the first action should be to contact all TD’s and Senators to tell them to vote no. I cannot emphasis how important this step is, because depending on whether the regulations are directly effective or not, the opt-in vote stage may be the only mechanism to stop the pact becoming law in Ireland.

I have been advised that template letters or emails will not work and will simply be disregarded, so I am not issuing a template letter, however, you will find a document in the description box with the names and contact details for all TD’s and Senators, and I would ask that you send whatever communication you feel is appropriate to them asking them to vote no to the opt-in to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact.

Step 2: In circumstances where both Houses vote to opt-into the new pact, the next step would be to try and secure an injunction to stop the State formally opting-into the pact, however, the chances of success of the injunction (in my view at least) largely depend on whether the regulations are directly effective or require transposing laws to be enacted.

Directly effective

As stated earlier, if the regulations are directly effective, legal action can only be initiated (in my view) after the opt-in is passed by the Houses of the Oireachtas but before the Government communicated its formal opt-in to the EU – because there is a chance that once the Government formally opt-in the necessitated obligations clause that we discussed earlier might be activated.

Given that time would be of the essence, the only mechanism that I can see available is an injunction to prevent the Government from formally opting-in – on the basis of the Crotty v An Taoiseach 1987 judgment, however, it is highly unlikely that this would be successful as Crotty refers to an unauthorised delegation of sovereignty in the area of foreign policy matters, noting that in Crotty it was held that “the powers must be exercised in subordination to the applicable provisions of the Constitution. It is not within the competence of the Government, or indeed of [the parliament], to free themselves from the restraints of the Constitution or to transfer their powers to other bodies unless expressly empowered so to do by the Constitution.” So, the net issue was whether or not the State could “enter into binding agreements with other states, or groups of states, to subordinate, or to submit, the exercise of the powers bestowed by the Constitution to the advice or interests of other states” and in Crotty it was concluded that “the State’s organs cannot contract to exercise in a particular procedure their policy-making roles or in any way to fetter powers bestowed unfettered by the Constitution.” – meaning that while the State’s external sovereignty could be exercised by the Executive, the Executive was not free to alienate this power, without an constitutional amendment.

This brings us to why Crotty is unlikely to be successful, and explains why I went through, in detail, the constitutional amendments agreed via the Referendums on Treaty of Amsterdam in 1998, the Treaty of Nice in 2002 and the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009.

Through these referendums, the Irish people voted on no less than 3 occasions to:

a) delegate its authority under the Constitution to the Houses of the Oireachtas to opt-in or not of EU laws in the area of freedom, security and justice, which includes both immigration and asylum and

b) to authorise the Houses of the Oireachtas to relinquish the opt-in provision entirely, without having to refer the matter to the people in a further referendum

So, Crotty is unlikely to apply given that Crotty refers to an unauthorised delegation of authority to relinquish sovereignty – in circumstances where in the present case the people have actually voted on this very issue on three separate occasions and on each occasion they have voted to delegate authority to the Houses of the Oireachtas.

As I said, an injunction using Crotty is possible the only legal mechanism available if the regulations are directly effective (but for the reasons explained Crotty is not likely to be successful – but if this was the only mechanism available, it should be explored further).

If the regulations are not directly effective and must be transposed into national law

In these circumstances, the legal avenues open to us improves significantly, as some or all of the 5 Regulations would have to go through the normal Irish legislative process, which would consist of 5 stages in Dail Eireann, which may or may not pass, 5 stages in Seanad Eireann which may or may not pass, but in circumstances where proposed Bills do pass both the Dail and Seanad, there is a possibility (depending on who the President of Ireland is at the time), that the President may refuse to sign the Bills and instead refer them to the Supreme Court to test their constitutionality or (and this is the preferred option) that it may be possible to call an Ordinary Referendum – which, it should be noted, has never happened since the 1937 Constitution was enacted.

So, there are two types of Referendums that can be held in Ireland, a Constitutional or an Ordinary Referendum, noting that every referendum held to date has been a constitutional referendum, which simply means a referendum to amend the Constitution. If Crotty applied and was successful, the end result would be a Constitutional Referendum, however, as I said I do not believe that Crotty applies in this case and the only chance of a referendum is an Ordinary Referendum.

An ordinary referendum is one that does not relate to amending the Constitution and would only occur if the President received a joint petition from both houses of the Oireachtas, stating that a proposed Bill was of such national importance that the people of Ireland should decide whether it became law. The joint petition would need majority support from the Seanad and one-third of the members of the Dáil would also have to support the petition. When the President received the petition, he would be obliged to consult the Council of State and if the President agreed that the proposal was of such national importance, he would refuse to sign the Bill until a referendum had been held.

So, if both Houses of the Oireachtas agree to opt-into the EU Migration and Asylum Pact and the 5 number regulations and if the regulations require transposing domestic laws to be enacted, an injunction could be sought after the opt-in was passed by the Houses of the Oireachtas but before the Government communicated its formal opt-in to the EU – because there is a chance that once the Government formally opt-in the necessitated obligations clause would become live.

The argument would, therefore be that the injunction was necessary precisely because the necessitated obligations clause would be triggered on formal opt-in thus making any future legislative challenge impossible and if the injunction was successful, or even if it was not successful, people would have the opportunity to again lobby TDs and Senators to vote no on passing of the domestic Bills needed to transpose the 5 regulations.

If these Bills were passed, there would still be an opportunity to lobby TD’s and Senators to file a petition to try and call an Ordinary Referendum, which as I said, would only be possible with majority support from the Seanad and support from one-third of the members of the Dáil. I understand that the 5 number regulations will not be in force for 2 years, meaning that each member state will have two years to put whatever laws and systems it needs to in place – so if these regulations need transposing domestic legislation, it is highly unlikely that this will be achieved in the lifetime of the current Government, and the makeup of the Dail and the Seanad could be significantly different after the next General Election – meaning that your vote at the next General Election has the potential to stop the EU Migration and Asylum Pact becoming law in Ireland.

To conclude:

Over the coming weeks, Helen McEntee will try to secure the necessary approvals from both Houses of the Oireachtas to opt-into the EU Migration and Asylum Pact and Regulations, and the legal avenues open to us to challenge the regulations is highly dependent on whether the regulations are directly effective in Ireland or whether the Government will need to enact domestic laws in addition to the regulations.

If the regulations are directly effective, the only legal mechanism I can see open to us is an injunction on the basis of the Crotty v An Taoiseach 1987 judgement but I do not think this would be successful for the reasons stated earlier. If the regulations require transposing laws to be enacted, there is a possibility that an injunction would be successful, but again, not on the basis of Crotty, but even if an injunction was not successful, there may be a possibility of calling an Ordinary Referendum should the necessary support be garnered from both Houses of the Oireachtas.

The best advice I can give at this time is to contact your TD’s and Senators today (and every day) to tell them to vote no to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact and once we know for certain whether the 5 regulations will be directly effective or not, I will provide a further update.

In summary, the concerns I have on the proposed regulations include the following:

With respect to the Eurodac Regulation – I would be concerned that once the infrastructure for a computerised central database for biometric data, and facial recognition is established and rolled out for one group of people, it is easily extended to cover all people, so you should question how long before such a system is proposed to be used for EU citizens too under the guise of safety and to ensure non-discrimination and equality of treatment between all persons.

With respect to the Screening Regulation – this regulation is said to extend regulation 2016/399 which applies to member states that are party to the Schengen acquis, given that Ireland is not part of the Schengen acquis, I do not see how we could opt into the screening regulation.

With respect to the Asylum Procedure Regulation – this regulation would introduce more restrictive requirements for determining both first countries of asylum and safe countries (both of which could have a significant impact on Irelands ability to return international protection applicants to other countries). Also, while the regulation says that Member States retain the ability to designate safe third countries in addition to those designated at an EU level, a Member State cannot designate as a safe country, a country that the EU has designated otherwise – so we would effectively lose control over what we consider to be a safe country.

With respect to the Asylum and Migration Management Regulation – this regulation would oblige Ireland to either accept relocation of a minimum of 30,000 asylum seekers annually, from other member states regardless of the fact that Ireland is not the first member state that the applicant entered (note that the figure of 30,000 is said to be the minimum figure that can be accepted annually), or pay a penalty of at least €600m annually.

With respect to the Crisis and Force Majeure Regulation – this regulation would allow member states in migratory crisis to apply for adjustments or derogations to the rules set out in the other regulations such as the level of contributions member states would have to make to the effected member state and insisting that relocation of asylum seekers is the primary or only solidary measure that the member state would accept.

There can be little doubt that the people of Ireland do not want the open borders policy that the Irish Government and the EU are pushing for, and that if this issue was put to the people they would vote no, so I have little doubt that the Government will put every obstacle in our way (including purposefully creating confusion as to whether transposing laws are required) to ensure these regulations become law, so we need to be sure that we exhaust every avenue at our disposal, and this starts with ensuring we know how these laws will be passed to make sure we can make an informed decision on the best steps to take.

Until then, please share this information with as many people as possible and ask them to contact their TDs and Senators to tell them to Vote No to the EU Migration and Asylum Pact.

Photo by Sora Shimazaki from Pexels

Photo by Sora Shimazaki from Pexels

Photo by Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash

Photo by Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash

Photo by note thanun on Unsplash

Photo by note thanun on Unsplash